VSP’s minimal magnetic signature ensures maximum safety

In March 2022, the passage through the Bosphorus – one of the most important shipping lanes in the world – had to be closed temporarily to civilian ships because of a floating sea mine. For four hours, the maritime bottleneck connecting the Mediterranean to the Black Sea was blocked while the dangerous explosive device was defused by specialists.

While the origin of the mine was never fully determined, the incident makes it clear that even civilian shipping far away from actual combat is still at risk from the Russian war of aggression. At the beginning of the hostilities, both parties to the conflict had already extensively mined the northern part of the Black Sea. Not all of these mines were reliably anchored, and some eventually broke loose and were carried away by ocean currents. As a result, reports of floating sea mines have been increasing ever since – threatening to detonate at any moment.

The Bosphorus marks the southern end of the Black Sea and is its only access to the Mediterranean. Since 1936, Turkey has been responsible for monitoring and securing the passage as stipulated in the Montreux Convention. Once the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine started, the scope of the resulting obligations increased considerably. Turkish Navy mine countermeasure vessels (MCMVs) patrol the country’s northern coasts almost around the clock – especially around the northern outlet of the Bosphorus. Operations like this one place high demands on the ships. Since modern sea mines are often equipped with magnetic detonators that react to changes in the surrounding magnetic field, the steel hull of an approaching ship or the magnetic field of its drive can trigger an explosion.

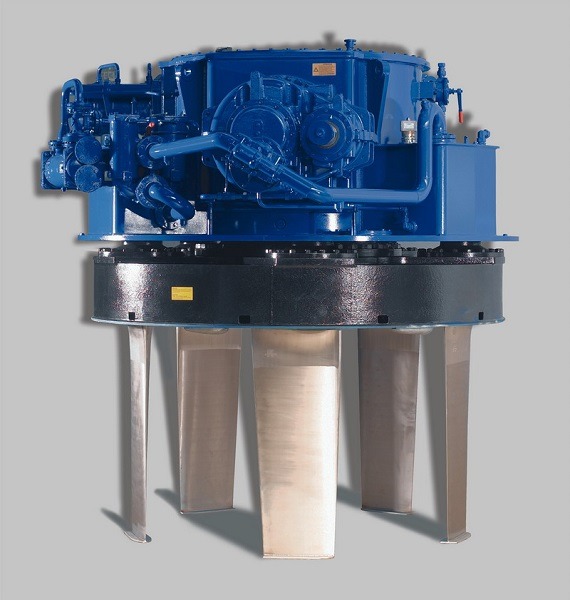

To minimize the magnetic signature, the hulls of many MCMVs are made of non-magnetic materials. While wood was the material of choice for this in the past, fiberglass or a special non-magnetic stainless steel is often used today instead. Care is also taken to ensure that the technical equipment only generates very low magnetic fields. That is why the Turkish Navy relies on the Voith Schneider Propeller (VSP) for its Aydin-class MCMVs.

The first ship in this class was built in Germany by Abeking & Rasmussen in the early 2000s. Five more of these minesweepers, each around 55 meters long, were later built at a shipyard in Istanbul. Non-magnetic steel was used as the hull material.

The two VSPs in the hull accelerate the Turkish MCMVs to speeds of up to 15 knots. Developed almost 100 years ago, the drive concept used for both propelling and steering the ship has an extremely low magnetic signature. This reduces the risk that an MCMV will be detected by magnetically triggered mines during surveillance missions. At the same time, the low noise emissions of the VSP also make it harder for acoustic mines to locate the ship. The drive system therefore guarantees maximum safety during operations in and around the Bosphorus. “Our technology allows the Turkish Navy to perform its tasks efficiently and safely,” says Oliver Lenz, Sales Application Manager Yachts & Navy at Voith Turbo.

Lenz goes on to point out another advantage of the drive concept: “The VSP offers outstanding dynamic positioning (DP) properties. The Antalya-class ships can therefore maintain their position very precisely even in strong ocean currents and systematically search a defined area for dangerous objects.” Two opposing currents coincide in the Bosphorus: Down to a depth of around 40 meters, a strong upper current flows toward the Mediterranean at average speeds of three to five knots – even up to eight knots when exacerbated by the wind strength and direction. Beneath this, a weaker countercurrent drifts toward the Black Sea. Precise DP is therefore essential for surveilling the strait reliably and safely, making the VSP an important element of protecting international shipping.